Roots of Contemporary Conflicts, Part 2. Divided Slavs and the Mongol Invasion

The Mongol invasions in 13th and 14th centuries contributed to the divisions among the Eastern Slavs and had a significant impact on events in Europe. However, the fall of Kiev and other important centres in the eastern region helped another city to rise. Which city was it? And what happened to the Mongols in Europe?

Contents

Tatar Rule

Batu Khan, who was Genghis Khan's grandson and his very capable successor, conquered several Turkic territories and the area roughly south of the Black Sea. Batu's army then sacked the successor states of Kievan Rus, including Kiev. He continued westward and divided his army into two parts, one of which defeated the Christian knights in Silesia (Lehnice), the other in Hungary (Mohi). Templars, too, joined the Christian armies defending against the Mongols.

In 1242, Batu Khan abandoned his westward expansion and returned to Mongolia to take part in the election of a new khan. At that time, he founded a state called the Golden Horde in the region of present-day Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan. The name ‘Golden Horde’ derives from the Turkic word orda, meaning "camp". The word "golden" was probably inspired by the way the Mongols marked cardinal directions: north - black, south - red, east - blue, west – white, and centre - yellow or gold.

Until the end of the 15th century, Batu's successors ruled modern-day southern Russia from the city of Sarai, which used the tax system inspired by China.

The Golden Horde was rapidly losing its exclusively Mongolian character and its power was gradually declining. The descendants of the Mongol rulers formed the ruling class, while their subjects were mostly Cumans, Tatars, Bulgars, Kirghiz and other Turkic tribes. In the 14th century, the descendants of Genghis Khan, already known as Tatars, embraced Islam.

Mongolian bow, used for centuries into the modern era

The Rise of Moscow and the Black Death

The invasion of the Mongols was fatal for the Eastern Slavs: Kiev and other sacked cities fell, while Novgorod and other cities began to flourish and prosper under Mongol rule. Moscow even became an independent principality in 1327.

As early as 1304, Prince Yuri of Moscow laid claim to the inheritance of Yaroslav the Holy. In 1332 Ivan I. Moscow paid tribute to the khan of the Golden Horde, and sacked Tver. The Khan rewarded him with the title of Grand Prince of Moscow, Vladimir and all Russia.

In 1349 a plague spread from Scandinavia, which struck Moscow in 1353, killing many, including some members of the princely family.

A Persian-style helmet used by the Tatars

On the Field of Kulikovo

The triumphs of Dmitri Ivanovich Donskoy, the prince of Moscow, most notably at the Battle of Kulikovo, contributed to the fall of the Golden Horde. On 8 September 1380, Dmitry defeated the army of Khan Mamay, reinforced by foreign mercenaries (incl. Genoese). However, the victory did not mean the fall of the Tatar rule, who continued to rule over Russia for one more century.

The Fall of Tatar Rule

Around the middle of the 15th century, the weakened Golden Horde split into five different khanates: the Khanate of Sibir, the Great Horde (the Nogai Horde), the Khanate of Kazan, the Astrakhan Khanate, and the Crimean Khanate. The common rival of the khanates was the Grand Duchy of Moscow.

By the end of the 15th century, the Moscow rulers defeated the Tatars and expanded their territory eastward. They were less successful in the west, where they encountered resistance from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (the successor of Novgorod).

Crimean Tatars

In the first half of the 15th century, several Tatar clans settled in Crimea. In 1441, the Khanate of Crimea was established, occupying almost the entire peninsula, as well as the Black Sea regions of Kherson, Nikolaev, Zaporozhye and Donetsk.

In the 1560s the Crimean Khanate came under the control of the Ottomans, who gradually took control of the Black Sea. Later the Ottomans pushed away the Genoese from Balaklava, Sudak and Kaffa (Feodosiya). The Sultan occupied the southern coast of the Crimean Peninsula, while leaving the Tatars in control of the inland plains.

Ukrainian Cossacks of the 17th century, Czech Republic (Huľajpolská kureň)

Cossack Uprisings

Since the end of the Middle Ages the duchies of Kiev, Braslav, Chernigov and others were controlled by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In 1596, it merged with Poland, forming the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita). The south-eastern provinces of the Rzeczpospolita were different from the others in many aspects.

The Poles began to refer to them as “Ukraine”. The Orthodox population was predominant over the Roman Catholic population in these regions, while in other parts of the country, the opposite was true. The nobility was divided into two distinct groups: a very small group of sovereign feudal lords, the rest was members belonging to the lower nobility class.

The most powerful lords owned vast numbers of villages and serfs, acting as autocrats with their own military troops. They exercised their influence at the royal court, controlled the local administration, and manipulated the Cossack chiefs. The members of lower nobility often allied themselves with the independent warriors, the Cossacks, because they shared a culture and religion with them.

In the 17th century, disagreements between the Catholic magnates and the Orthodox Ukrainians culminated. Several rebellions were brutally suppressed, and the situation of the Cossacks got worse. However, in 1648, Bohdan Khmelnitsky appeared, and things began changing. The intelligent military commander of Ukrainian Cossacks decided to change the fate of the Cossacks and convinced the elders to revolt.

Khmelnitsky knew from previous uprisings that the Cossack army stood no chance in a direct confrontation with the forces of the Rzeczpospolita, and that Polish retaliation would be terrible.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth after the Truce of Andrusovo (1667). The territory on the right was given to Moscow. (Arre Caballo)

He asked for help from the Russian Tsar, but the tsar refused because he did not want to start a conflict with the powerful Rzeczpospolita. The Cossacks allied with the Crimean Tatars, who provided 5,000 men under the experienced commander Tuhai Bey. In addition, Khmelnitsky had the fighters from Zaporozhye, and he assumed that many other fighters will join as the uprising advances.

When the news of the death of King Władysław IV of Poland and the news of the Cossacks victories reached Russia, the Russian army decided to march west. Moscow saw the Cossack rebellion as an opportunity to reclaim previously lost territories and perhaps even conquer the Ukraine. In 1650, Moscow declared war on the Rzeczpospolita.

Moscow's claims outraged the Crimean khan, who abandoned the Cossacks and joined the Rzeczpospolita. But the Rzeczpospolita wasted its chance, and after the victory at the Battle of Berestechko (1651), they suffered a terrible defeat at Batih (1652).

On October 1, 1653, Tsar Alexei I summoned a provincial congress, which approved the annexation of Ukraine to Russia. This decision was approved by the Ukrainian Cossack council on 17 October.

In 1654 Bohdan Khmelnitsky paid tribute to Tsar Alexei, and Moscow granted patronage to Ukraine. This act is considered the end of the Cossack uprising and the beginning of the long Polish-Russian war.

The so-called Left-bank Ukraine (i.e. beyond the left bank of the Dnieper), including Kiev, was finally annexed to Russia in 1667.

This state of affairs lasted for more than 100 years (not counting the brief period 1708-1709, when some Ukrainian Cossacks under Ivan Mazepa joined the Swedes fighting against Tsar Peter I). After the partitions of the Rzeczpospolita (1772, 1793, 1795), 80% of the territory of Ukraine belonged to the Russian Empire, the rest to the Habsburg Monarchy.

The Crimean peninsula, controlled by the Turks and Tatars, was conquered by Russian troops at the end of the 18th century. After a brief period as a state (1917-21), Ukraine became part of the USSR. This remained the case until the end of the 20th century

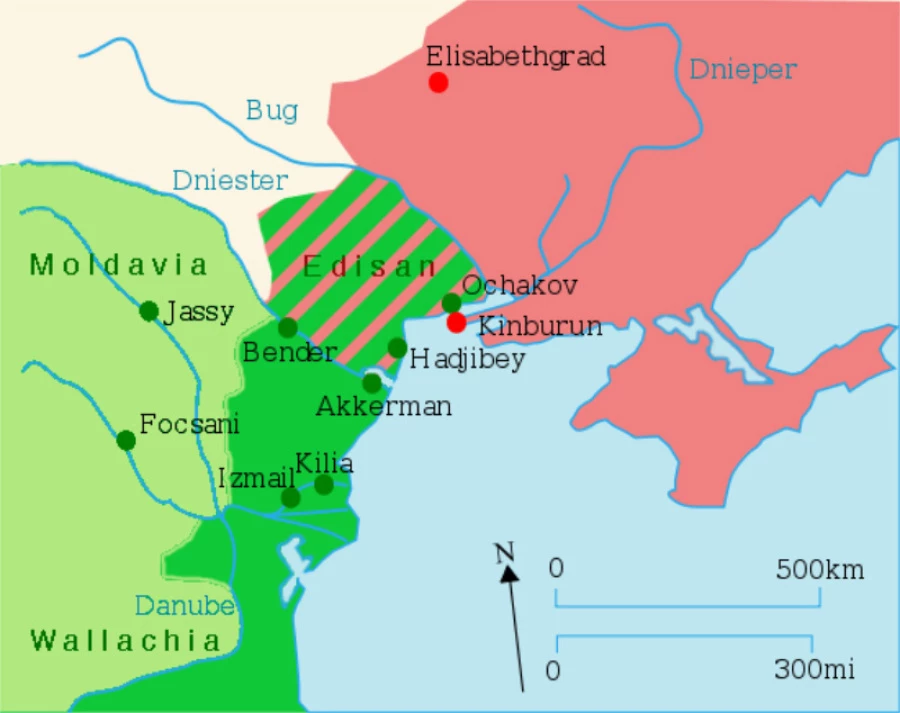

A map showing the outcome of the 1791/92 Treaty of Jassy. The right part belonged to Russia. (Wikipedia)

In the following article, we will look into the Ukrainian military system.

Cover photo: Bashkirs and Cossacks performed by the KVH KP.

Comments